Issue #23 of LFG: Learning from Games is the topic for which I named this section of the newsletter — can we take what we learn in games and apply them in the real world? Read on to find out!

Hello JOMT Reader!

We use video games in many different ways from entertainment and stress relief, to teaching and learning. While we’ve been enjoying games for its entertainment value for many years, its use in education is much more recent, with a vast majority of studies about video games in education being published in the past 10–15 years. These games, collectively known as serious games, have been great for imparting bits of knowledge to its players.

But we now live in a world where knowing things isn’t enough. Back in the 20th century when I was in school (I can say that, right?) knowing things was how people got labelled “smart.”1 A walking encyclopedia was the business class ticket to success in school. Fast forward to the 21st century and anyone with an internet connection can know things, or at least find them out.

Others have recognized this shift and have coined a term to refer to a set of skills that are necessary for success in today’s world: 21st Century Skills (or 4Cs). These skills — creativity, critical thinking, collaboration, and communication — are seen as valuable components for success in the global economy.

So where do video games fit into 21st Century Skills? To answer this question, we need to know how these skills have been defined2:

Creativity encompasses the generation of new and valuable ideas, the refinement and evaluation of these ideas, the ability to work creatively with others, and the persistence to implement and promote these ideas despite obstacles and failures.

Critical thinking is the disciplined process of effective reasoning, systematically analyzing, and evaluating evidence to make reasoned judgments, solve problems, and draw conclusions.

Communication is the multi-faceted ability to effectively convey and interpret messages in various forms and contexts, utilizing a strong command of language, an understanding of cultural nuances, and the deployment of verbal and non-verbal cues.

Collaboration is the coordinated effort of individuals to interact effectively, respect and integrate diverse perspectives...and achieve common goals through active listening, clear communication, and responsible, ethical leadership.

If you think about these skills in the context of video games, you’re probably using them every time you play. In single player games, you might not be communicating or collaborating with others but you are definitely exercising your creative and critical thinking muscles. In multiplayer games, communication and collaboration are key components for victory.

The big question is whether we can get the 4Cs practised using video games out into the real world. This process is called skills transfer (or sometimes transference) — getting skills from practise (context #1) to application (context #2). Research has shown that the similarity of context #1 and #2 matters: more similar contexts tend to transfer skills better and is called near transfer. An example might be skills gained in a flight simulator that is then applied when flying the real thing.

On the other end of the spectrum is far transfer, where the context of practised skills and applied skills differ greatly. An example might be problem-solving skills gained in video games being applied to real-world strategic problems.

Given the importance of the 4Cs and the fact that they can be practised while playing video games, the researchers wanted to know if they could transfer these skills into the real world. Could we eventually include our video game experience on our resumes as a valid source of transferable skills?

How did the researchers study transferable skills?

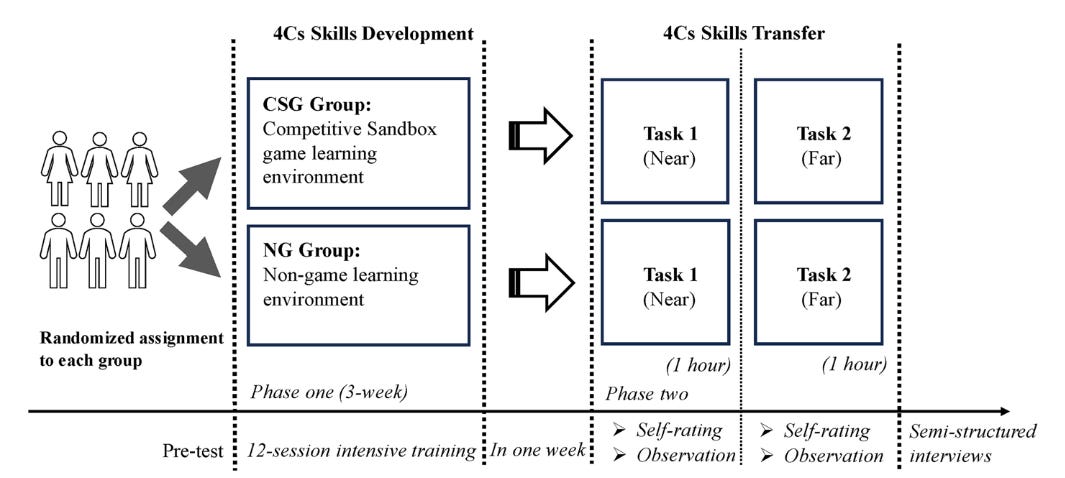

To study how skills transferred from video games to real life scenarios, the researchers divided 110 university students into two groups: one group received training for the 4Cs in a traditional manner with an instructor, while the other group trained these skills using a video game called Shadows of Doubt. This game is described as a sandbox detective game where players have to work together to solve a mystery.

Both groups received training for three weeks, after which they were assessed on how well the 4C skills transferred to both near (similar scenario as their training) and far (completely different scenario from their training) contexts.

Too early to include video games on a resume…for now

Unfortunately, the results aren’t all that promising. For skills applied to similar scenarios (near transfer), none of the 4C skills trained using Shadows of Doubt except for collaboration, transferred differently when compared to the traditionally trained group. Only collaboration transferred better when trained with video games when compared to their textbook counterparts.

The same was true for skills when applied to a different scenario (far transfer). For this scenario, both the video game-trained and textbook-trained groups were asked to apply their skills to design a business strategy. Again, only collaboration emerged with a measurable difference.

What does this all mean?

On the surface, it looks like there’s no benefit to training creativity, critical thinking, and communication skills using video games. Certainly, it’s too soon to be able to include “video games” as a transferable skill on a resume. But what’s going on?

One of the big limitations of this study is how skills transfer was measured. Or more precisely, how long participants had to apply their trained skills. For both groups, only one hour was provided for them to use their skills. It was hardly enough time to digest the new situation (even for near transfer contexts) and figure out how to apply the 4Cs.

What the experiment didn’t account for was the stages of team development that leads to a measurable outcome. Creativity, critical thinking, and communication skills may take time to manifest. A better measure of whether video games were effective in transferring the 4C skills is to measure how quickly the video game-trained group arrives at a solution to a problem. The difference in using video games versus textbooks for training 4C skills might come down to how quickly they can be adapted to a different scenario. Another difference might be seen in the quality of solutions as these skills are applied.

Another issue that the researchers note is that the classification of near and far transfer might be too primitive to capture the nuances associated with how skills are transferred. There are a whole host of other factors, like motivation and interest, that affects how well skills transfer from gaming to non-gaming contexts. Like many things, it isn’t as binary as near and far.

Final remarks

One day, I would love to include “played XCOM” under the skills section of my resume and have it count as a valid measure of transferable skills. But we aren’t there yet.

To get there, we’ll need a follow-up study on other factors — like how quickly 4C skills can be applied after video game training — that can measure how well skills transferred from video games. Another interesting study would be to compare the speed and quality of solutions based on the genre of video games. Maybe FPS players arrive at a solution faster but strategy players’ solutions are higher quality when these 4C skills are applied.

My hunch is that video game players are quicker to recognize patterns of thought and behaviour through the 4C skills, which in theory should speed up and increase the quality of solutions to the problems that they are trying to solve. But we’ll have to wait for someone to do the experiments and confirm or disprove my hunch!

If you want to read more about this study, you can access the article here for free: https://educationaltechnologyjournal.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s41239-024-00500-2#Sec7

If you liked what you read, please consider giving this post a like and sharing it with your community!

I was not a very good student back then because I couldn’t get my head around this concept of knowing things (wasn’t there a GI Joe saying back then “Knowing is half the battle”?). I did much better on the small portion of tests that asked questions about applying the knowledge.

These definitions have been taken from https://educationaltechnologyjournal.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s41239-024-00500-2, the study that this post is based on.

Interesting, as always! I suspect the transfer effect is much stronger if the player already has a knack or talent, plus an active interest, in what the skill involves. I've seen that with some gamers, to a degree.